Emily Tian

Cy Twombly: Making Past Present at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Jan. 14 - May 7

I Know a Man

As I sd to my

friend, because I am

always talking,— John, I

sd, which was not his

name, the darkness sur-

rounds us, what

can we do against

it, or else, shall we &

why not, buy a goddamn big car,

drive, he sd, for

christ’s sake, look

out where yr going.

— Robert Creeley, 1962

I have been hooked by this poem for years. Composed of a single sentence, almost entirely monosyllabic, with vowels shorn off in the manner of a teen’s texting habits, “I Know a Man” is a poem of extreme compression. Within thirty seconds it’s over. Like a witness to a badly paced punchline or a minor miracle, I can’t help but feel like I’ve been played.

I was reminded of Creeley a few days ago when I was in Boston to catch a Cy Twombly show at the Museum of Fine Arts before it closed. It turns out that Creeley and Twombly had both been influenced by their time in the 1950s at Black Mountain College, an experimental liberal arts school in North Carolina. There, as a weekend interloper in and around Harvard Yard, on Stanley Cavell’s old stomping grounds, I began thinking about the way Twombly, Creeley, and Cavell — occupants of the same grand and tremulous century, neighbors of shared places, people, and texts — could be appraised together.

Stanley Cavell, the American philosopher who died in 2018, was enthralled by Hollywood, bewitched by jazz, and counted among his many interlocutors Wittgenstein, J.L. Austin, Thoreau, Emerson, Shakespeare and Beckett. From Cavell we learn that communication is inseparable from community. Language fords us from senseless isolation toward a community of speakers, where the criteria under which meaning is assayed is determined deliberatively, by the group we are part of, thus also by us ourselves as representatives of that group. I am, while speaking freely, always sticking my neck out, subjecting myself to the possibility that others disagree with the claims that I am making, or worse, that those with whom I am speaking have no basis at all to understand me, that I make no sense. This is an enterprise that each of us endures in the daily activity of speech, despite the likelihood of reprobation and critique, and before we imagine ourselves heroic for doing so — though in no small measure we are — let us not forget (I hear Cavell soberly intoning) that there is no other path we can take. Cavell writes, rather insists: “The alternative to speaking for myself representatively (for someone else’s consent) is not: speaking for myself privately. The alternative is having nothing to say, being voiceless, not even mute.”

Born in 1926 in Arlington, Massachusetts, the same year as Cavell, Creeley briefly flitted around literary circles at Harvard before leaving to drive an ambulance in the American Field Service during the war. Upon his return, he grew close with Charles Olson, the poet whose manifesto connecting poetry to openness and breath, “Projective Verse,” became something of a founding document for the Black Mountain Poets, a group of writers affiliated with Black Mountain College. The school had been for a short but brilliant run the site of an explosive concatenation of modernist literature and art (among its alum: Josef and Anni Albers, Roberts Creeley, Motherwell and Rauschenberg, Ruth Asawa, John Cage, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller). Twombly, just two years younger than Creeley, never directly overlapped with him at Black Mountain as a student there in 1951, but he also befriended Olson, who succeeded Albers as the school’s rector.

I’d like to suggest that Creeley and Twombly can be understood to express Cavellian standards: communication as a quest for community, the truth of skepticism, knowing as acknowledging. In “I Know a Man” the poet motions us over, saying, in effect: let me tell you about something that happened to me the other day, this conversation I was having with a friend. But moments after the easygoing introduction we are dealt two blows in rapid succession: first, we learn that the speaker is talking to his friend because of his own uncontrollable garrulousness (not, as one might expect, because they are close confidantes); second, we learn that John is not his friend’s real name. So what is it? Why conceal it from us? I know a man. Does he really? Taken in by an assertive, brassy title — the claim of knowledge — we suddenly find ourselves in the middle of the woods with strange company. As Creeley’s voice halts at the end of each line, we are reminded of the fragility of the formal devices we erect against the threat of the unintelligible. The poem veers right into the speaker’s question, which is simultaneously a recognition of our precarity, a plea for sense-making, and a temptation for a sedative escape (we could choose to live grandly and carelessly, à la cadillacs and Sant Ambroeus — why not?). Then, without so much as a pause, Creeley’s profoundly vulnerable moment of uncertainty is eclipsed by his friend’s impatient command: this isn't the time to philosophize, focus on staying on the road, keeping us alive.

Is it tragic that not-his-name John does not seriously entertain the speaker’s question? I don’t think so. Recall Wittgenstein in the Tractatus: “The solution to the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of this problem.” We find our bearings philosophically by renewing our attention to how our worlds are ordinarily constituted, how the life of his friend is casually entrusted in his hands. “The” is transfigured by a chest-thumping “this.” Here the skeptical recital comes to a close. His friend’s reply is exactly the answer he needs: his anxiety accompanying the discovery of darkness is displaced by the bare fact that he has to pay attention to the wheel.

Cavell writes, “This skeptical picture is one in which all our objects are moons. In which the earth is our moon. In which, at any rate, our position with respect to significant objects is rooted, the great circles which establish their back and front halves fixed in relation to it, fixed in our concentration as we gaze at them. The moment we move, the parts disappear, or else we see what had before been hidden from view - from any other position than one perpendicular to that great circle, that ‘back half’ which alone established can be seen: to establish a different ‘back half,’ a new act of diagramming will be required, a new position taken, etc.”

In other words: our precarious perceptual situation is characterized by the fact that all we can ever really see (hence, know) are surfaces, which screen off the backside and interior of that which we are observing. Insofar as the external world and the private experiences and thoughts of other people are fundamentally mysterious to us, the skeptic possesses the upper hand. But Cavell subverts skepticism’s traditional kinship with cynicism by recognizing its positive phenomenological character. Our inability to understand others, or the fear that we do not, is not a mere signal of our lack of mutual attunement but also a source of motivation for continuing to learn how to relate to and recognize other people by acknowledging the claims they make upon us. While there remains the devastating possibility of being disappointed by those with whom we seek to understand, the alternative — utter isolation — is far worse. So the primitive form of communication is trust. Language is an invitation to project our imagination to construct a world in which we are intelligible to each other.

In Twombly, as in Creeley, we follow the skeptic’s path from knowledge toward acknowledgment. The recent show at the Museum of Fine Arts, which ran from January to May, gathered together photographs, ancient art from the museum’s collection as well as from Twombly’s personal collection, and Twombly’s own body of work, demonstrating Twombly’s lifelong engagement with the myth and culture of Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and Near Eastern antiquity. One of the most celebrated and challenging artists of the American post-war generation, Twombly is known for his chalkboard-like scrawls, asemic scribbles and improvisational strokes of color. But unlike his contemporaries in New York, Twombly spent many of his mature years in Rome and Gaeta, a small town along the Tyrrhenian coast, impressed by the Mediterranean sea and the visions of ancient history around him.

In a 1972 piece for Artforum, Rosalind Krauss repeats a story about the art critic and historian Michael Fried, who tells a Harvard undergraduate in the Fogg Museum, “There are days when [Frank] Stella goes to the Metropolitan Museum. And he sits for hours looking at the Velazquez, utterly knocked out by them and then he goes back to his studio. What he would like more than anything else is to paint like Velazquez. But what he knows is that that is an option that is not open to him. So he paints stripes.”

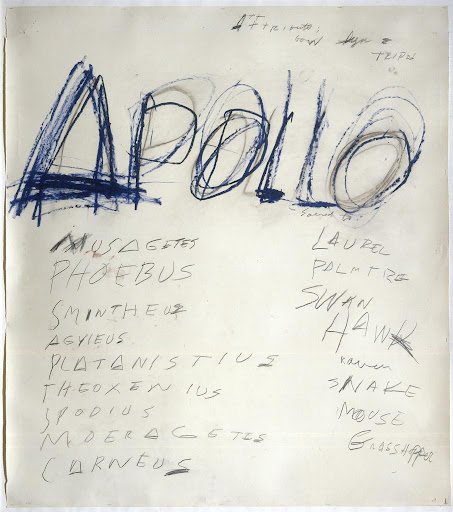

Modern, hence perpetually aware of his own lateness, Twombly turns to his available option: painting names. By taking up traditionally textual questions of meaning and language in the pictorial plane, he dodges the relentless march toward flatness that was the fate of some of his contemporaries. His 1979 painting “Orpheus” is dominated mostly by a shakily crayoned O — an inhalation, an invocation, a katabasis, a tragic return. And in his 1975 painting “Apollo,” the name is spreadeagled across the top of the canvas like a blue tent propped up by a two-column list of the god’s other names and representations (on the left: Musagetes, Phoebus, Smintheus, Agyieus, Platanistius, Theoxenius, Spodius, Moeragetes, Corneus; on the right: Laurel, Palm Tree, Swan, Hawk, Raven, Snake, Mouse, Grasshopper).

Apollo, 1975, Cy Twombly, courtesy of Cy Twombly Foundation.

What’s in a name, anyway? It is a bare, linguistic signifier, cleft from physical embodiment and conceptual depth, not dissimilar to the surface of an object. Staring at a pale canvas on which a single scrawled name has been placed, one may very well take Twombly to be the paradigmatic representation for modern art’s spiritual vacuity, where knowing no longer can be prised apart from name-dropping. A few biographical details do not help Twombly’s case: a placard next to the Coronation of Sesostris, a cycle of paintings that recalls the story of a historical Egyptian pharaoh, admits that Twombly was more interested in the sound of his name than his deeds. There is his incredible, cosmopolitan lifestyle: he married Tatiana Franchetti, an Italian baroness and the sister of his patron, lived in an august Roman palazzo, and traveled extensively to Morocco, Cuba, Mexico, Egypt, Turkey, Russia, Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, and India. And then there is that embarrassing admission that Twombly never took up learning Latin or Greek himself, despite heavily quoting from the likes of Sappho and Catallus.

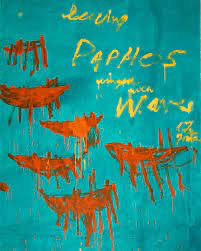

Leaving Paphos Ringed with Waves (III), 2009, Cy Twombly, courtesy of Cy Twombly Foundation.

But if the omnipresence of surfaces is an abiding expression of skepticism, let it also be recognized that they are the places we make our homes. Cavell, again: the earth is our moon. When we learn to speak as children, newly initiated into linguistic conventions, we know next to nothing about the meanings of the words we are pronouncing. (Think of a child, petulant or blank-faced, parroting the word grief.) We start with names and only deepen our concepts gradually as we become accustomed to the world. In his paintings of names and lyric fragments, Twombly enacts a self-conscious fantasy of knowledge where the vacancies of a largely irrecoverable past, once acknowledged, become an open field for participation. In that sense, his work doubles as an eloquent salute to Cavafy, Rilke, and every other stubbornly immovable tenant of antiquity’s ruins.

When I was at the MFA my friend nudged me to look at a thirty-some-year-old woman walking around the show with her daughter, pointing out the boats on the aqueous blue-green canvas of “Leaving Paphos Ringed with Waves.” And they are unmistakably boats, completely legible to a little kid: gestural oars, a roguish, dripping orange, sure, but boats nonetheless, on their way from Paphos toward wilder shores. In spite of his difficulty, Twombly was someone who could speak the language of children and knew exactly how to remind us of our permanent exile from that kingdom.

Orpheus, 1979, Cy Twombly, courtesy of Cy Twombly Foundation.